Coronavirus is in the air—particularly indoor air. Eight months into this pandemic response and the science has confirmed more strongly the airborne risks of COVID-19: from early instances of restaurant patrons catching coronavirus from other tables, to super-spreading events that defied any six-foot boundary that coronavirus may abide by, to the World Health Organization reversing its position that coronavirus was not airborne (after hundreds of scientists petitioned the body), to, most recently, the Centers for Disease Control stating that coronavirus is airborne and can linger in the air for hours. At this point, it’s asymptomatic people just talking or breathing who are responsible for a large portion of spreading the virus. And the leading airborne transmission experts are calling on us to improve indoor ventilation and filtration.

What rightly worries employers is the risk that their building’s air systems start blowing coronavirus-laden particles all around the office and infecting people—so much so that the nation’s leading experts on ventilation systems have assembled a task force and issued guidance to upgrade buildings’ ventilation systems to reduce coronavirus infection rates. Wearing masks and maximizing physical distance are first-deployed strategies. But it doesn’t stop there.

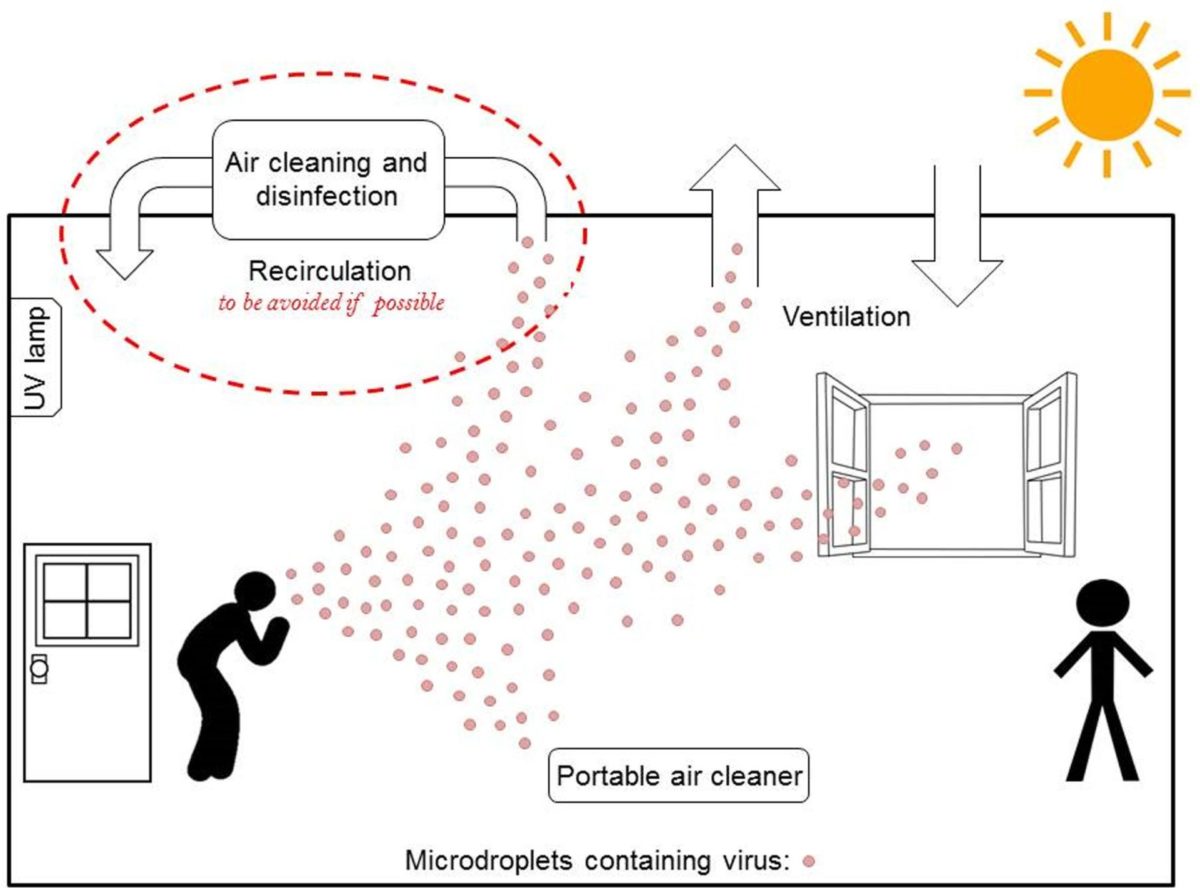

Cleaning the air is a critical part of drawing down infection risks—arguably more important and challenging than just cleaning surfaces. Changing out the air in a building more frequently and using higher grade filters are key strategies. Those filters are the mechanical equivalent of lungs for a building, and we want those artificial lungs to catch the virus before ours do.

But existing air systems can be tweaked only so far before reaching their limits. And that calls for no small task: upgrading the heating, venting, and air-conditioning (HVAC) system itself.

We have the opportunity before us to solve two problems at once. These HVAC systems are the single largest consumer of dirty energy in the built environment. For too long, our HVAC retrofit ambitions have been stifled by the disruption it would present. Unfortunately, we now have this disruption. We need to utilize this moment and make health-protective HVAC upgrades that save energy. We can at the same time address the very near-term public health threat along with the ever-growing climate crisis threat.

That said, unthinkingly retrofitting HVAC systems will actually put us deeper in the hole. Installing appliances that light fossil fuels on fire, like gas-fired appliances, is detrimental to our health and climate. We shelter in place and work from home to reduce risk of coronavirus transmission. But if we are forced to breathe dirty air inside (from cooking or heating), our efforts are working at cross purposes. Tragically, breathing polluted air is statistically linked to higher COVID-19 death rates, possibly one of the most important contributors. Instead, by installing clean electric appliances—think electric, not gas, stoves—that provide healthier living conditions, we can advance, not inhibit, the fight against coronavirus.

Also, we also cannot treat our essential workers who install these clean energy solutions as if their health, safety, and wellbeing are inessential. Workers will enter homes and businesses more than 15 million times over the next year just to replace failed heating devices. We must ensure we have adequate health protocols for contractors to minimize health risks during the installation process. Another critical strategy is virtualizing as much of the retrofit as possible: audit, permit, inspection, rating, and critically measuring the energy savings at the meter. Innovative thought leaders already are advancing these efforts.

Pandemics have already changed the course of architecture through the present. And this first modern pandemic has rightly catapulted indoor air quality to the top of our minds and that of building scientists. Like the precursors to this pandemic, we should heed this warning and plan—including making the long-term investment—for the future fleet of post-pandemic buildings. For example, California just put a $600 million down payment on upgrading ventilation systems in schools, giving the California Energy Commission the opportunity to demonstrate these dual climate and health wins. These pandemic-planned buildings, done right, will drive down climate emissions in the building sector more than any other single opportunity.